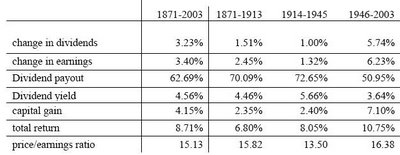

This article provides various data which it purports to relate to dividends and valuations for the S&P 500 dating back to 1871.* As shown in the chart below, dividends increased an average of 3.23% per year between 1871 and 2003. However, this average increase was not uniform. The chart below divides the dividend increases into three periods: (a) 1871-1913, (b) 1914-1945, and (c) 1946-2003. Between 1871 and 1913, dividends increased an average of 1.51% annually, between 1914 and 1945 they increased about 1.00% annually, and between 1946 and 2003 they increased an average of 5.74% annually. The dividend increases have accelerated further since 2003, as discussed in a previous post.

The annual dividend increases since 1946 have been very impressive. This highlights the reason why I am a strong believer that dividend-paying stocks should comprise a portion of every investor's portfolio. In fact, I believe that dividend-paying stocks are far more attractive than bonds for young investors (e.g., investors under 35 or 40 who will likely participate in the workforce for 20+ more years) for several reasons.

First, dividend income is generally taxable at a maximum rate of 15% a year as opposed to bond payouts which are generally taxed as ordinary income (i.e., at a tax rate of up to 35% for an individual). Second, dividend-paying stocks offer a great potential for capital gains not provided by bonds. For example, in the event that the earnings for the companies paying dividends keep increasing, there is a likelihood that their associated stock prices will also rise and that their dividend payouts will increase accordingly. Bonds, on the other hand, pay the same interest payout amounts year-after-year.

Finally, dividend-paying stocks provide some protection against inflation that bonds necessarily cannot provide. The prevailing view holds that as inflation heats up companies raise prices and the revenue from the inflated prices is reflected as increased company earnings. As earnings increase, the corresponding stock prices and dividends generally increase accordingly, as discussed above. However, during such inflationary periods, bonds become less valuable. For example, a 5% payout may be attractive when inflation is running at 1% per year, but are far less attractive when inflation accelerates to 6% per year.

*This data cannot be correct, however, as the S&P 500 index was only created in or around 1923. I presume that the data prior to 1923 must have come from a similar index of large-cap stocks.

2 comments:

That was very interesting. The graph you have really lays it out nicely.

Actually the S&P 500 was created in 1957 with 500 constituent securities.

Standard and Poors developed a series of indices back in 1923 covering around 223 securities.

So, it depends whether the S&P 500 index methodology/constituent rules were extended back before 1957 or whether the data is simply those 223 securities 1923 onwards until 1957.

Post a Comment